Female Circumcision; FGM, female circumcision, female circumcision in Islam, is a public resource in response to such concepts as vaginal Aesthetics was formed for the purpose of the blog. Blogs do not reflect the author's personal opinion, already has a personal opinion "information" it is not as values. The information that is considered essential to inform the correct block has been tried to show the source. Sincerely ...

WHERE KESER in female genital mutilation

Female circumcision has two different application: the clitoris is cut and application of cutting deep cut on the clitoris is removed only. 1-clitoris is cut application. The cuts made by the members of the tribal beliefs and religions in Africa. There are varieties of its own. The lightest of the clitoris (clit) is completely cut off. Or clit has inner and outer lips together çıkarılmı or varieties such as the removal of heavier as the entrance to the vagina. No matter what sort of reduces the sexual pleasure of women or completely eliminate it. This "circumcision" to name as it is essentially wrong. Female Genital Mutilation (FGM Female Genital Mutilation) is more accurate to call the. In Pharaoh also called the Sunna. In ancient Egypt, God proclaimed and implemented by themselves oppressed peoples of the Pharaohs. At that time, "Egypt of the Pharaohs" was super-state views were also strong and cultural domains beyond political boundaries. Middle East and Africa, was coming to the cultural domain of the Egyptian Empire. Menstrual emerged in Egypt as soon as implemented in the form of affectation of other neighboring countries and tribes, there were pharaohs of Egypt to him in an enviable view of the country. That's basically where female circumcision clitoris is cut, the era of the Pharaohs in Egypt Taking spread to Africa and the Middle East.

The clitoris is cut "Pharaoh Sunnah of" origin is ancient Egypt.

Shandal 1963 a large number of archaeologists working "Pharaoh's circumcision"

female mummy was found applied. This process class in ancient Egypt

It was made to highlight the difference. Shandal BC 5th century in this process

Africa reports that spread from Ancient Egypt. Mummies found

or completely cut off the genitals of blinded by planting a portion

(Infibulation) has cut the clitoris of the majority.

Applications where 2-clitoris cut. Only cutting off the piece of skin covering the clitoris is an application that revealed the head of the clitoris. Just as "male circumcision" as in n. Never cut the clitoris is removed by cutting the overlying skin. After marrying the girl of this application is made to take much pleasure from sexual intercourse. In this way quicker than girls who were circumcised and fulfilled live orgasm. This application in the US and Europe "clitoral Hoodectomy" is applied in the name of aesthetic surgery centers. In addition, the practice of female circumcision in Islam is like that.

Dinlerde klitoris kesimi

Klitoris kesimi özellikle orta Afrika'da olmak üzere çeşitli din mensuplarınca uygulanabilmektedir.Afrika kabile dinleri

Klitoris kesimi özellikle orta Afrika kabile toplumlarınca yapılan bir uygulamadır.[1] Afrika geleneklerine göre klitoris kesimi kadının temizliği ve saf bir anne olabilmesi için gereklidir. Klitoris kesimi yapılmamış kadınların evlenmesini doğru karşılamazlar. Bazı kabileler ise çocugun doğum sırasında kesilmemiş klitorise değmesi durumunda öleceğine inanırlar.[9]Yahudilik

Etiyopya Yahudi Topluluğu (Beta Israel) tarafından dini olmayan bir törenle uygulanmaktadır. Ancak kesimin Yahudi bir kadın tarafından yapılması şartı vardır.[10]İslam

Kadın sünneti, İslam dininin dîni bir vecibesi değildir. Birçok insanın bu olayı İslam ile ilişkilendirdiği, ama yapılan araştırmalar sonucu ortaya çıkan gerçeğin ; kadın sünnetinin herhangi bir din tarafından desteklenmediği, buna rağmen " birçok dîni lider tarafından insanların bu işleme mahkum edildiği, dolayısıyla uygulamanın dîni engelleri geçtiği " anlatılmakta ve uygulamanın; Müslüman, Hıristiyan ve Yahudi inancına sahip topluluklarda olabildiği belirtilmektedir.[11]Bu inançların hiçbirisinin kadın genital uzvunun kesilmesini desteklemediği hatta gerçekte; İslam Şeriatının, çocukları ve onların haklarını koruduğu vurgulanmaktadır. Kadın sünneti uygulaması yapılan ülkelerden: Etiyopya, Fildişi Sahili, Senegal, Kenya, Benin ve Gana'da yaşayan Müslüman nüfus gruplarının, Hıristiyan gruplara nazaran daha fazla kadın sünneti uygulama olasılığının yüksek olduğu; Nijerya, Tanzanya, ve Nijer'de ise, uygulama yaygınlığının Hıristiyan gruplar arasında daha çok olduğu ifadesi yer almaktadır.[11]

Bu ifadeler kadın sağlığı üzerine yapılmış ciddi araştırma sonuçları üzerine düzenlenen yayınlarda yer almaktadır.[12]

Bazı Afrika müslüman toplumlarında kadın genital uzvunda kesim yapılması (kadın sünneti) olayı,[13] bazı araştırmacılar tarafından daha çok " Afrika gelenekleri " kaynaklı olduğu şeklinde açıklanır.[14]

İslâm'da kadın genital uzvunun kesilmesinin yeri hakkında âlimler arasında bir görüş birliği yoktur. Ancak, islama aykırı olmadığını iddia edenler tarafından temel dayanak olarak Ebu Davud'da yer alan bir hadis gösterilmektedir.[15] Ebu Davud kitabında bu hadisin rivayet zincirinde kopukluklar olduğunu ve zayıf olduğunu da belirtmiştir. "Dünya Müslüman Ulemalar Birliği" genel sekreteri ve El Ezher Üniversitesi üyesi Dr. Muhammad Salim al-Awwa klitoris kesiminin islam da yeri olmadığını iddia eder ve zayıf bir hadise dayanarak hüküm verilmesini rededer.[16]

Circumcisers, methods

Anatomy of the vulva, showing the clitoral glans, clitoral crura, corpora cavernosa and vestibular bulbs

When traditional circumcisers are involved, non-sterile cutting devices are likely to be used, including knives, razors, scissors, glass, sharpened rocks and fingernails.[31] A nurse in Uganda, quoted in 2007 in The Lancet, said that a circumciser would use one knife to cut up to 30 girls at a time.[32] Depending on the involvement of healthcare professionals, the procedures may include a local or general anaesthetic, or neither. Women in Egypt reported in 1995 that a local anaesthetic had been used on their daughters in 60 percent of cases, a general in 13 percent and neither in 25 percent.[33]

Classification

Typologies

The WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA issued a joint statement in April 1997 defining FGM as "all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs whether for cultural or other non-therapeutic reasons."[34]The procedures vary considerably according to ethnicity and individual practitioners. During a 1998 survey in Niger, women responded with over 50 different terms when asked what was done to them.[23] Translation problems are compounded by the women's confusion over which type of FGM they experienced, or even whether they experienced it. Several studies suggest survey responses are unreliable. A 2003 study in Ghana found that in 1995 four percent said they had not undergone FGM, but in 2000 said they had, while 11 percent switched in the other direction. In Tanzania in 2005, 66 percent reported FGM, but a medical exam found that 73 percent had undergone it.[35]

Standard questionnaires ask women whether they have undergone the following: (1) cut, no flesh removed (pricking or symbolic circumcision); (2) cut, some flesh removed; (3) sewn closed; and (4) type not determined/unsure/doesn't know.[36] The most common procedures fall within the "cut, some flesh removed" category, and involve complete or partial removal of the clitoral glans.[37]

WHO Types I–II

The WHO has created a more detailed typology, Types I–III, based on how much tissue is removed; Type III is "sewn closed." Type IV describes symbolic circumcision and miscellaneous procedures.[38]Type I is subdivided into Ia, removal of the clitoral hood (rarely, if ever, performed alone),[39] and the more common Ib (clitoridectomy), the complete or partial removal of the clitoral glans and clitoral hood.[40] (When discussing FGM, the WHO uses clitoris to refer to the clitoral glans, the visible tip of the clitoris.)[41] Susan Izett and Nahid Toubia write: "[T]he clitoris is held between the thumb and index finger, pulled out and amputated with one stroke of a sharp object."[42]

Type II (excision) is the complete or partial removal of the inner labia, with or without removal of the clitoral glans and outer labia. Type IIa is removal of the inner labia; IIb, removal of the clitoral glans and inner labia; and IIc, removal of the clitoral glans, inner and outer labia. Excision in French can refer to any form of FGM.[43]

Type III

Type III (infibulation or pharaonic circumcision), the "sewn closed" category, involves the removal of the external genitalia and fusion of the wound. The inner and/or outer labia are cut away, with or without removal of the clitoral glans. Type IIIa is the removal and closure of the inner labia and IIIb the outer labia.[44] The practice is found largely in Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan (though not South Sudan) in northeast Africa. Estimates of numbers vary: according to one in 2008, over eight million women in Africa have experienced it.[13] According to UNFPA in 2010, 20 percent of women with FGM have been infibulated.[12]Comfort Momoh, a specialist midwife, writes of Type III: "[E]lderly women, relatives and friends secure the girl in the lithotomy position. A deep incision is made rapidly on either side from the root of the clitoris to the fourchette, and a single cut of the razor excises the clitoris and both the labia majora and labia minora."[45] In Somalia the clitoral glans is removed and shown to the girl's senior female relatives, who decide whether enough has been amputated. After this the labia are removed.[46]

A single hole of 2–3 mm is left for the passage of urine and menstrual fluid by inserting something, such as a twig, into the wound.[47] The vulva is closed with surgical thread, agave or acacia thorns, or covered with a poultice such as raw egg, herbs and sugar.[48] The parts that have been removed might be placed in a pouch for the girl to wear.[49] To help the tissue bond, the girl's legs are tied together, often from hip to ankle, for anything up to six weeks; the bindings are usually loosened after a week and may be removed after two.[50] Momoh writes:

[The entrance to the vagina] is obliterated by a drum of skin extending across the orifice except for a small hole. Circumstances at the time may vary; the girl may struggle ferociously, in which case the incisions may become uncontrolled and haphazard. The girl may be pinned down so firmly that bones may fracture.[45]If the remaining hole is too large in the view of the girl's family, the procedure is repeated.[51] The vagina is opened for sexual intercourse, for the first time either by a midwife with a knife or by the woman's husband with his penis. In some areas, including Somaliland, female relatives of the bride and groom might watch the opening of the vagina to check that the girl is a virgin.[52] Psychologist Hanny Lightfoot-Klein interviewed hundreds of women and men in Sudan in the 1980s about sexual intercourse with Type III:

The penetration of the bride's infibulation takes anywhere from 3 or 4 days to several months. Some men are unable to penetrate their wives at all (in my study over 15%), and the task is often accomplished by a midwife under conditions of great secrecy, since this reflects negatively on the man's potency. Some who are unable to penetrate their wives manage to get them pregnant in spite of the infibulation, and the woman's vaginal passage is then cut open to allow birth to take place. ... Those men who do manage to penetrate their wives do so often, or perhaps always, with the help of the "little knife." This creates a tear which they gradually rip more and more until the opening is sufficient to admit the penis.[53]The woman is opened further for childbirth and closed afterwards, a process known as defibulation (or deinfibulation) and reinfibulation. Reinfibulation can involve cutting the vagina again to restore the pinhole size of the first infibulation. This might be performed before marriage, and after childbirth, divorce and widowhood.[54]

Type IV

The WHO defines Type IV as "[a]ll other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes," including pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterization.[1] It includes nicking of the clitoris (symbolic circumcision), burning or scarring the genitals, and introducing substances into the vagina to tighten it.[55] Labia stretching is also categorized as Type IV.[56] Common in southern and eastern Africa, the practice is supposed to enhance sexual pleasure for the man and add to the sense of a woman as a closed space. From the age of eight, girls are encouraged to stretch their inner labia using sticks and massage. Girls in Uganda are told they may have difficulty giving birth without stretched labia.[57]A definition of FGM from the WHO in 1995 included gishiri cutting and angurya cutting, found in Nigeria and Niger. These were removed from the WHO's 2008 definition because of insufficient information about prevalence and consequences.[56] Gishiri cutting involves cutting the vagina's front or back wall with a blade or penknife, performed in response to infertility, obstructed labour and several other conditions. Over 30 percent of women with gishiri cuts in a study by Nigerian physician Mairo Usman Mandara had vesicovaginal fistulae. Angurya cutting is excision of the hymen, usually performed seven days after birth.[58]

Complications

Short-term and late

FGM harms women's physical and emotional health throughout their lives.[59][60] It has no known health benefits.[10] The short-term and late complications depend on the type of FGM, whether the practitioner had medical training, and whether she used antibiotics and unsterilized or surgical single-use instruments. In the case of Type III, other factors include how small a hole was left for the passage of urine and menstrual blood, whether surgical thread was used instead of agave or acacia thorns, and whether the procedure was performed more than once (for example, to close an opening regarded as too wide or re-open one too small).[9]

FGM ceremony in Indonesia

— Stephanie Sinclair, The New York Times[61]

Late complications vary depending on the type of FGM.[9] They include the formation of scars and keloids that lead to strictures and obstruction, epidermoid cysts that may become infected, and neuroma formation (growth of nerve tissue) involving nerves that supplied the clitoris.[66][67] An infibulated girl may be left with an opening as small as 2–3 mm, which can cause prolonged, drop-by-drop urination, pain while urinating, and a feeling of needing to urinate all the time. Urine may collect underneath the scar, leaving the area under the skin constantly wet, which can lead to infection and the formation of small stones. The opening is larger in women who are sexually active or have given birth by vaginal delivery, but the urethra opening may still be obstructed by scar tissue. Vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistulae can develop (holes that allow urine or faeces to seep into the vagina).[9][68] This and other damage to the urethra and bladder can lead to infections and incontinence, pain during sexual intercourse and infertility.[66]

Painful periods are common because of the obstruction to the menstrual flow, and blood can stagnate in the vagina and uterus. Complete obstruction of the vagina can result in hematocolpos and hematometra (where the vagina and uterus fill with menstrual blood).[9] The swelling of the abdomen that results from the collection of fluid, together with the lack of menstruation, can lead to suspicion of pregnancy. Physician Asma El Dareer reported in 1979 that a young girl in Sudan with this condition was killed by her family.[69]

Pregnancy, childbirth

External images

Neonatal mortality is increased. The WHO estimated in 2006 that an additional 10–20 babies die per 1,000 deliveries as a result of FGM. The estimate was based on a study conducted on 28,393 women attending delivery wards at 28 obstetric centres in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal and Sudan. In those settings all types of FGM were found to pose an increased risk of death to the baby: 15 percent higher for Type I, 32 percent for Type II and 55 percent for Type III. The reasons for this were unclear, but may be connected to genital and urinary-tract infections and the presence of scar tissue. The researchers wrote that FGM was associated with an increased risk to the mother of damage to the perineum and excessive blood loss, as well as a need to resuscitate the baby, and stillbirth, perhaps because of a long second stage of labour.[73]

Psychological effects, sexual function

According to a 2015 systematic review there is little high-quality information available on the psychological effects of FGM. Several small studies have concluded that women with FGM suffer from anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.[65] Feelings of shame and betrayal can develop when women leave the culture that practises FGM and learn that their condition is not the norm, but within the practising culture they may view their FGM with pride, because for them it signifies beauty, respect for tradition, chastity and hygiene.[9]Studies on sexual function have also been small.[65] A 2013 meta-analysis of 15 studies involving 12,671 women from seven countries concluded that women with FGM were twice as likely to report no sexual desire and 52 percent more likely to report dyspareunia (painful sexual intercourse). One third reported reduced sexual feelings.[74]

Distribution

Prevalence

Further information: Prevalence of female genital mutilation by country

Prevalence in 15–49 age group

Percentage aged 15–49 with FGM in the 29 countries in which it is concentrated (UNICEF 2014).[5] Also see map of Africa.

Egypt, Ethiopia and Nigeria had the highest number of women and girls living with FGM as of 2013: 27.2 million, 23.8 million and 19.9 million respectively.[77] (Egypt outlawed FGM in 2007, Ethiopia in 2004 and Nigeria in 2015.)[78][79][7] In 2014 prevalence rates for women in sub-Saharan Africa were 39 percent and for girls aged 0–14, 17 percent. For Eastern and Southern Africa the figures were 44 and 14 percent, and for West and Central Africa 31 and 17 percent.[5]

Prevalence figures are based on household surveys known as Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), developed by Macro International and funded mainly by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS), conducted with financial and technical help from UNICEF.[80] These have been carried out in Africa, Asia, Latin America and elsewhere roughly every five years, since 1984 and 1995 respectively.[81][82]

The first survey to ask about FGM was the 1989–1990 DHS in northern Sudan, and the first publication to estimate FGM prevalence based on DHS data (in seven countries) was by Dara Carr of Macro International in 1997.[83] A UNICEF report based on over 70 of these surveys concluded in 2013 that FGM was concentrated in 27 African countries, Yemen and Iraqi Kurdistan,[84] and that 133 million women and girls in those 29 countries had experienced it.[3]

Outside the 29 key countries, FGM has been documented in India, the United Arab Emirates, among the Bedouin in Israel, and reported by anecdote in Colombia, Congo, Oman, Peru and Sri Lanka.[85] It is also practised in Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia and Malaysia, and within immigrant communities around the world, including Australia, New Zealand, Europe, Scandinavia, the United States and Canada.[86]

Ethnicity

A country's national prevalence often reflects a high sub-national prevalence among certain ethnicities, rather than a widespread practice.[88] In Iraq, for example, FGM is found mostly among the Kurds in Erbil (58 percent prevalence within age group 15–49), Sulaymaniyah (54 percent) and Kirkuk (20 percent), giving the country a national prevalence of eight percent.[89]The practice is sometimes an ethnic marker, but may differ along national lines. In the northeastern regions of Ethiopia and Kenya, which share a border with Somalia, the Somali people practise FGM at around the same rate as they do in Somalia.[90] But in Guinea all Fulani women responding to a survey in 2012 said they had experienced FGM,[91] against 12 percent of the Fulani in Chad, while in Nigeria the Fulani are the only large ethnic group in the country not to practise it.[92]

Rural areas, wealth, education

Surveys have found FGM to be more common in rural areas, less common in most countries among girls from the wealthiest homes, and (except in Sudan and Somalia) less common in girls whose mothers had access to primary or secondary/higher education. In Somalia and Sudan the situation was reversed: in Somalia the mothers' access to secondary/higher education was accompanied by a rise in prevalence of FGM in their daughters, and in Sudan access to any education was accompanied by a rise.[93]Type of FGM

Women are asked during surveys about the type of FGM they experienced:[94]Most affected women experience one of the "cut, some fleshed removed" procedures, which embrace WHO Types I and II.[37] Types I and II are both performed in Egypt.[95] Mackie wrote in 2003 that Type II was more common there,[96] while a 2011 study identified Type I as more common.[97] In Nigeria Type I is usually found in the south and the more severe forms in the north.[98]

- Was the genital area just nicked/cut without removing any flesh?

- Was any flesh (or something) removed from the genital area?

- Was your genital area sewn?

Type III (infibulation) is concentrated in northeastern Africa, particularly Djibouti, Eritrea, Somalia and Sudan.[99] In surveys in 2002–2006, 30 percent of cut girls in Djibouti had experienced Type III, 38 percent in Eritrea and 63 percent in Somalia.[100] There is also a high prevalence of infibulation among girls in Niger and Senegal,[101] and in 2013 it was estimated that in Nigeria three percent of the 0–14 age group had been infibulated.[102] The type of procedure is often linked to ethnicity. In Eritrea, for example, a survey in 2002 found that all Hedareb girls had been infibulated, compared with two percent of the Tigrinya, most of whom fell into the "cut, no flesh removed" category.[103]

Age conducted

FGM is not invariably a rite of passage between childhood and adulthood, but is often performed on much younger children.[104] Girls are most commonly cut shortly after birth to age 15.[4] In half the countries for which national figures were available in 2000–2010, most girls had been cut by age five.[4] Over 80 percent (of those cut) are cut before that age in Nigeria, Mali, Eritrea, Ghana and Mauritania.[105] The 1997 Demographic and Health Survey in Yemen found that 76 percent of girls had been cut within two weeks of birth.[106]The percentage is reversed in Somalia, Egypt, Chad and the Central African Republic, where over 80 percent (of those cut) are cut between five and 14.[105] Just as the type of FGM is often linked to ethnicity, so is the mean age; in Kenya, for example, the Kisi cut around age 10 and the Kamba at 16.[107]

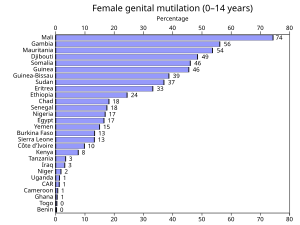

Changes in prevalence

In 2013 UNICEF reported a downward trend in over half the 29 key countries in the 15–19 group compared to women aged 45–49.[108] Little difference was found in countries with very high prevalence, but the rate of FGM had declined in countries with lower prevalence, or less severe forms of FGM were being practised.[109] According to UNICEF in 2014, the likelihood of a girl experiencing FGM was overall one third lower than 30 years ago.[110]In 2010 the DHS and MICS surveys began asking women about the FGM status of all their living daughters.[115] As of 2014 (right), the surveys suggested a prevalence for the 0–14 age group of 0.3 percent in Benin at the lowest (7 percent for the 15–49 group) to 74 percent in Mali (89 percent for 15–49).[5]

In a study in Egypt in 2008–2010 (FGM was banned there by decree in 2007 and criminalized in 2008), 4,158 women and girls aged 5–25, who presented to three departments at Sohag and Qena University Hospitals, replied to a questionnaire about FGM. According to the researchers, the most common form of FGM in Egypt is Type I. The study found that, between 2000 and 2009, 3,711 of the subjects had undergone FGM, giving a prevalence rate of 89.2 percent. The incidence rate was 9.6 percent in 2000. It began to fall in 2006 and by 2009 had declined to 7.7 percent. After 2007 most of the procedures were conducted by general practitioners. The researchers suggested that the criminalization of FGM had deterred gynaecologists, so general practitioners were performing it instead.[97]

Reasons

Support from women

Dahabo Musa, a Somali woman, described infibulation in a 1988 poem as the "three feminine sorrows": the procedure itself, the wedding night when the woman is cut open, then childbirth when she is cut again.[116] Despite the evident suffering, it is women who organize all forms of FGM, including infibulation. Anthropologist Rose Oldfield Hayes wrote in 1975 that educated Sudanese men living in cities who did not want their daughters to be infibulated (preferring clitoridectomy) would find the girls had been sewn up after their grandmothers arranged a visit to relatives.[117] Gerry Mackie compares FGM to footbinding. Like FGM, footbinding was carried out on young girls, nearly universal where practised, tied to ideas about honour, chastity and appropriate marriage, and supported by women.[118]

1996 Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography

A series of 13 photographs of an FGM ceremony in Kenya won the award:

Photograph 5

Photograph 7

Photograph 10

Photograph 13

Photograph 5

Photograph 7

Photograph 10

Photograph 13

— Stephanie Walsh, Newhouse News Service[119]

In communities where infibulation is common, there is a preference for women's genitals to be smooth, dry and without odour, and both women and men may find the natural vulva repulsive.[123] Men seem to enjoy the effort of penetrating an infibulation.[124] There is also a belief, because of the smooth appearance of an infibulated vulva, that infibulation increases hygiene.[125] Women regularly introduce substances into the vagina to reduce lubrication, including leaves, tree bark, toothpaste and Vicks menthol rub. The WHO includes this practice within Type IV FGM, because the added friction during intercourse can cause lacerations and increase the risk of infection.[126]

Common reasons for FGM cited by women in surveys are social acceptance, religion, hygiene, preservation of virginity, marriageability and enhancement of male sexual pleasure.[127] In a study in northern Sudan, published in 1983, only 558 (17.4 percent) of 3,210 women opposed FGM, and most preferred excision and infibulation over clitoridectomy.[128] Attitudes are slowly changing. In Sudan in 2010 42 percent of women who had heard of FGM said the practice should continue.[129] In several surveys since 2006, over 50 percent of women in Mali, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Gambia and Egypt supported FGM's continuance, while elsewhere in Africa, Iraq and Yemen most said it should end, though in several countries only by a narrow margin.[130]

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder